[Post by Dario Marino and Alessandro Riva]

Ultimately, the goal of economics should be to understand the functioning of society so well as to maximize each individual’s wellbeing.

And what better way to measure it than happiness? It is no mystery then, that as time went by, studies trying to measure cross-country happiness and linking it to some economic variable have flourished.

The subfield of Happiness Economics was first explored by Richard Easterlin in a 1974 paper, whose "Happiness Paradox” framework still dominates the field. I remember being introduced to him in my first Microeconomics undergraduate course, so he really was influential. After having crunched some data, Easterlin’s main conclusion is:

Within countries there is a noticeable positive association between income and happiness—in every single survey, those in the highest status group were happier, on the average, than those in the lowest status group. However, whether any such positive association exists among countries at a given time is uncertain.

The second sentence is what is commonly referred to as “The Paradox”. Interestingly, Easterlin himself doesn’t refer even a single time to this fact as a “Paradox”.

The claim to which the success of the paper is owed is that, while rich people tend to be happier than poor people within a country, no such relationship is found between rich and poor countries. Thus, the paper has since become a sort of manifesto for the “GDP doesn’t matter” line of thinking championed still today by many degrowthers. More generally, the fact that raising absolute levels of GDP per capita may not matter for our happiness, or that there exists a satiation point above which increasing income is pointless is obviously a troubling finding for Economics.

It’s unfortunately quite irrelevant that the paper has been debunked, because its main idea (which wasn’t even claimed by Easterlin himself) that GDP growth won’t make us happier (even though, it will) has permeated a sizeable fraction of the public.

What we’d like to address today is the methodology of happiness studies: we’ll first take a look at subjective self-reports, which are the main way these data is gathered; we’re going to address some of the problems linked to them; finally, we’ll take a look at one promising objective measure.

Stuck in subjectivity

Since Economists most of the times enjoy at least trying to be scientific, it’s clear that they would resort to subjective measures only if they have no other choice. It is the case for the study of Happiness.

Objective measures of happiness are already there, but they are mostly collective. Life expectancy, literacy, consumption. We need something that is tied to the individual. What about the amount of laughter that an individual has throughout an average year? Today “the average adult laughs 17 times a day while a child laughs 300 times a day”.

The fact that we now have personalized jesters available at every minute of the day would probably make us think that we are improving on this measure; however, historical data would be necessary to look into long-term trends. Good luck finding how many times Henry VIII laughed per day.

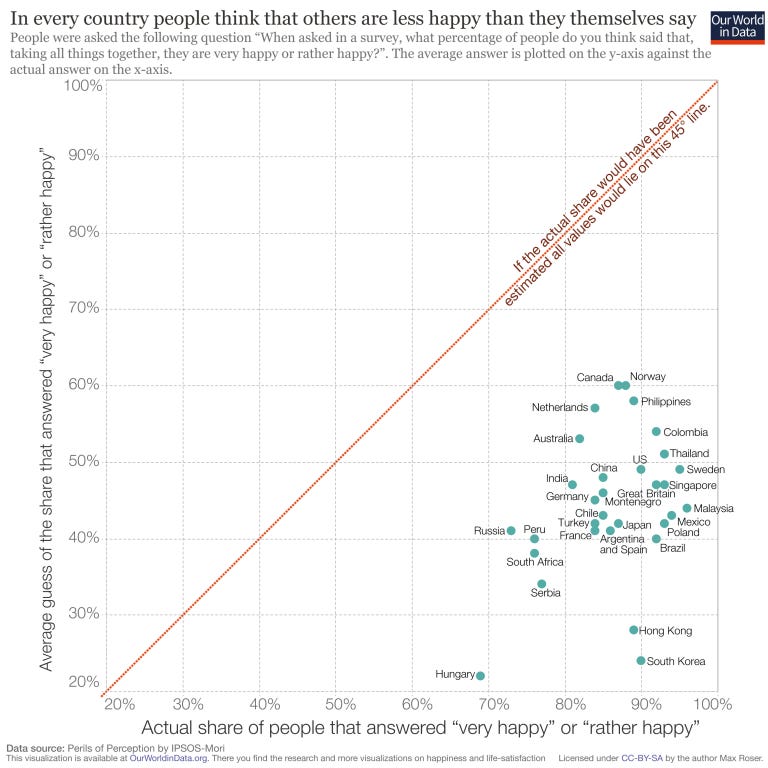

If we look at the happiness section of Our World In Data we can find a few interest graphs of happiness over time that all back the hypothesis of increasing happiness (with the US as one of the few that goes against this trend). However, these measures are all based on subjective self reports:

Subjective, self-reported measures present a variety of flaws that make them at least suspicious to a social scientist. We’ll present the ones we think are the most damaging:

Since all respondents place themselves in a normal distribution of happiness, their response will always be relative. It will be relative not only to their population, but even to their income bracket and their neighborhood. Indeed, we see that 5% of people that earn 500k per year consider themselves poor. Therefore, to measure progress we can’t rely on relative measures of happiness, because they will mostly be normally distributed.

It is possible however to compare between countries, depending on how questions are framed. If pollsters try to enlarge the scope of the respondents’ judgment from their social circle to the worst possible life and the best possible life in general, individuals will distribute taking into account people in other countries, enabling raw comparisons between countries.

If we’d like to build time series, we should keep in mind that comparing happiness between different generations cannot be robust. The sample that answered past questions is composed of dead people that did not compare their life standards with the people that are currently answering the questions. For this reason, we can only compare the happiness of respondents in a single poll at a given time. To compare between centuries we would have to come up with an absolute measure, a task which seems incredibly daunting both on theoretical and empirical grounds.

Every normal distribution of reported scores will feature people which feel more miserable than the average due to pre-determined genetic factors. This is not to say that some people are bound to be sad, but rather that people with a low set-point for happiness will react with a 5% increase in happiness to a 20% increase in income, while a high set point individual will react with a 20% increase in happiness to a 20% increase in income.

Moreover, they will be miserable in different ways depending on the society that they are placed in. The choice is yours: demigod that kills herself, or ditzy middle class teen with healthy weight consciously looking for comparisons on Insta to feel miserable. It is hard to improve the state of “genetically sad” individuals because, compared to the average person, they require more resources per capita to consider themselves happy. To put it in another way, their biologically determined set point will fluctuate depending on their personal circumstances, but nothing will be able to shift the happiness set point itself. However, we can still improve their absolute happiness, and that’s what we should worry about if we want to maximize aggregate welfare, because that will improve the situation for all individuals, including those that can absorb more easily the positive feelings coming from economic improvement.

Therefore, subjective measurements are bound to be static, since miserable people will be hard to lift up. Miserable here comes with no value judgment. Being part of the "Sad People" is not a question of success but more a question of predisposition.

The more we become wealthier, the more people can worry about new problems, for example their mental health. It is not strange to recognize “modern” forms of personality disorders in the more powerful and wealthy individual of the past, mostly melancholia, which is the term that evolved in our modern concept of depression. This suggests that growing concerns over the Mental Health epidemic are partly to be explained by humans simply becoming rich enough to afford free time to depress themselves over social media.

The fact that we once didn’t have the time and tools to recognize mental health disorders doesn’t make them less real or painful today.

However, this obviously creates problems for comparisons over time, as modern (rich) people have time to be aware of mental health issues a medieval peasant couldn’t even imagine.

Different cultures may have different views of the concept of happiness. For example, it may be socially more acceptable to confess being sad in a culture than in another, where maybe happiness signals higher status for some reason. Or maybe, due to imperfect translations, in other languages the concept we assign to “Happiness” could be misled for “Satisfaction” or “Peacefulness”.

Moreover, we can’t exclude the possibility of the framing and subjects of questions posed in surveys being biased due to researchers being mostly WEIRD.

After having read Joseph Henrich’s excellent book on the topic, we’re skeptical that one question could fit all the world’s different shades of the concept of happiness.

In order to properly analyze the problems tied to subjective self-reporting, it is also useful to take a look at the world’s most famous happiness yearly poll, that conducted by Gallup. Their methodology is the following:

Gallup asks people to imagine a ladder, with the lowest rung representing the worst possible life and the highest rung representing the best possible life. People rate where they stand today and where they expect to stand in five years. Based on how they respond, Gallup classifies them as thriving, struggling or suffering.

We can immediately notice that what this question measures would best be described as “Life Satisfaction” rather than “Happiness”. This is clearly our subjective opinion, but we would say that when each year headlines come out saying that Finland is once again the “Happiest country on earth” what people imagine is that in Finland people always smile, laugh, and enthusiastically party together all the time.

Anybody who ever encountered a nordic person knows that’s not how it works. This is probably due to Gallup’s question measuring how much people are satisfied with their life, rather than day-to-day joyfulness, which we think resembles more what people think when they picture “Happiness”. Finland is the world’s happiest country according to the World Happiness Report, which uses the same Gallup question to create a comparable score.

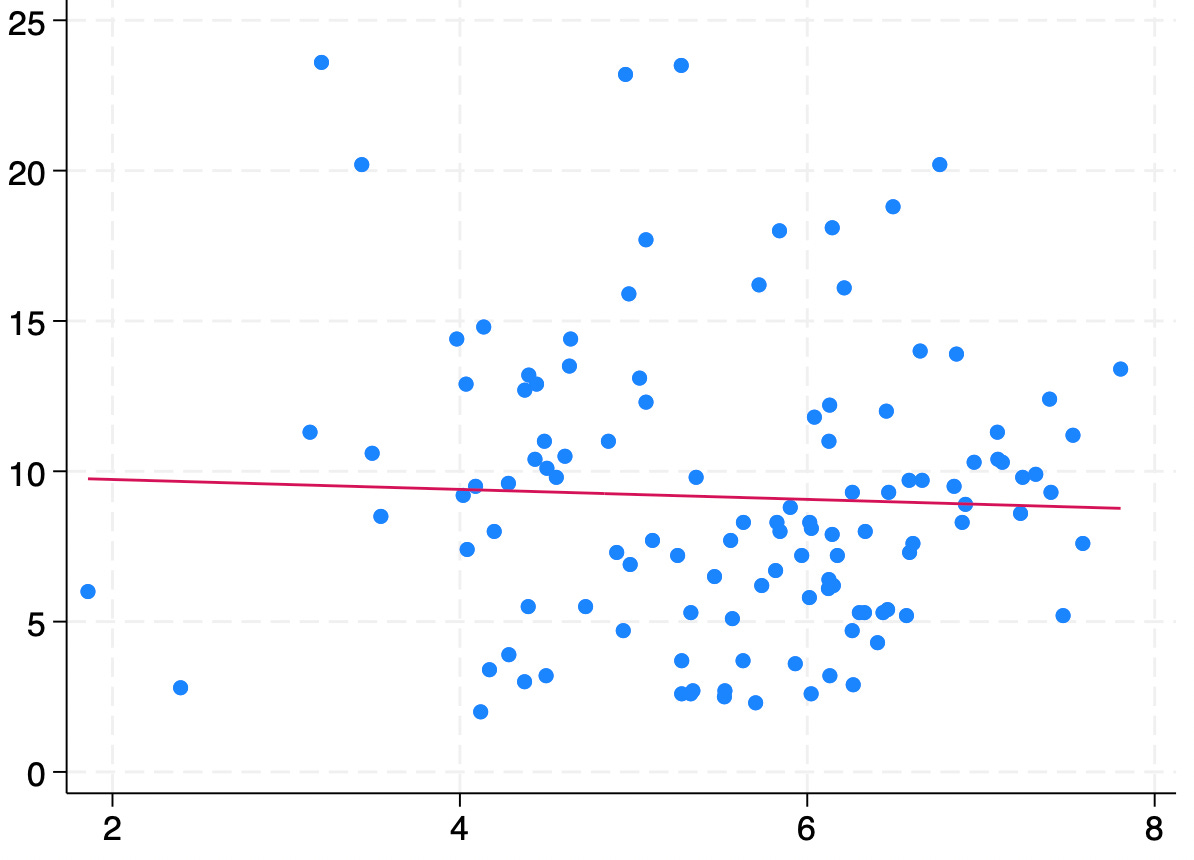

However, this doesn’t prevent it to be placed 38th out of 183 countries on the suicide rate ranking. To investigate further, we ran a regression of suicide rates (per 100,000 people) on the Report’s score (0-10). Not surprisingly, we didn’t find the negative relationship one should look for to claim the report efficiently measures happiness.

The correlation is instead extremely weak.

We can also find that the Report index doesn’t inversely correlate with loneliness indexes. Hardly anyone would associate persistent loneliness to Happiness. Nevertheless, a quick look at the map below shows no distinguishable association of loneliness with income or Happiness scores.

The Nordic champions of happiness self-report high loneliness across all ages, while supposedly sad Africans seem to be lonely at most during adolescence.

We don’t mean to be nihilistic here. Having data like the one produced by the report is always useful and interesting. However, if an Happiness score can’t even closely predict whether people are so miserable they are often lonely or kill themselves, we can surely say that they’re not measuring the right thing.

Once again, this doesn’t mean that the Gallup report isn’t measuring anything. It is probably a good measure of what we could call “Satisfaction” or “Tranquility”. It is likely that Nordic countries rank so high because they are rich, peaceful, stable and safe. People there have high incomes, nobody is unemployed, war is a relic of the past, and crime is low. On the other side of the ranking, we find unstable, war-torn violent countries like Afghanistan and the DRC, as well as countries that are just incredibly poor like Malawi. Our guess here is that this index is pretty good at measuring Stability, but this is still far from what most people would call happiness.

To conclude, it is quite funny to find that the same measure who claims it’s necessary to “move beyond GDP” since:

World leaders, including those in countries like Germany and New Zealand, are now recognizing the limitations of GDP. They realize how important improving and sustaining high wellbeing is to the health and economy of the people and nations they lead.

moves on to behave like this when regressed onto GDP:

Clearly, whatever this index means, it can be improved by improving GDP. Not a big surprise here, but given the GDP-skepticism aroused by the Happiness Economics literature it is a fact which may be worth remembering.

Time use is underrated

In the quest for objective measures of happiness, there are no clear candidates. Even though it is patently correlated to happiness, nobody serious would suggest that GDP per capita alone can measure it. The best objective measure we can think of is Time Use. It is also vastly underrated.

The key insight today is revealed preferences. We extensively explained the problems linked to subjective self-reported scores. After a quick tour of the subjective/heterodox literature on the issue, the main takeaway is that objective measures aren’t so bad after all. Maybe to measure happiness we don’t have any better choice than to agree on things that the majority of the population would consider unpleasant and trying to minimize them.

One such thing is obviously work and its counterpart, leisure: standard economic models take as an assumption that people dislike working and enjoy leisure time without loss of generality. It really is a fact so widespread that we can assume it without detaching too much from reality. Using (mostly) OECD data, we can even try to sketch a model to create an alternative happiness index.

We’re going to make some arbitrary assumptions that seem reasonable to us.

It’s safe to say that most people enjoy seeing friends (f) and that, humans being social animals, staying with people we like should be related to happiness. Thus, “Seeing friends” enters the equation with a +1.5 coefficient.

Other leisure activities (l), Eating and Drinking (e), personal care (p), are usually enjoyable and enter the equation with a +1 coefficient.

Housework and shopping (s) is a bit tricky because there are some people (for reasons mysterious to us) that actually enjoy it, so we’re going to attach it a -0.3 coefficient.

Other unpaid work (u) is also difficult: some people like it, but it is still work, although not as painful as your “real” job, so a -0.5 could do.

Sleeping is neutral. We’re not experts enough on the subject to judge what the optimal sleeping time is.

We’re also going to consider education neutral, because disentangling the fact that kids generally dislike it and its clear long-term benefits would be too complicated.

Work (w) is bad. Really bad. -1.5.

Thus, our Happiness (H) index ends up looking like this:

H=1.5*f+l+e+p-0.3*s-0.5*u-1.5*w

Unfortunately, since data is available only for 33 countries, we can’t compute global statistics. After having normalized our “H score” between is 0 and 1, here is our challenger leaderboard.

To make it comparable with the Gallup score, we also regressed it onto suicide rates.

Keep in mind that this is only a small subset of countries, which is also biased toward high incomes since most of them are OECD. It would be extremely interesting to have more data on Time Use around the world.

Nevertheless, our index seems to predict suicide rates a little better; it’s still a pretty weak correlation, but it’s at least noticeable. The ranking of countries seems more tied to common perceptions, too. It is not radically different from the Gallup one. However, the top spots are no longer occupied by Nordic countries, but rather by mediterranean ones, which, honestly, makes more sense to us.

We are clearly in the realm of subjectivity here (frankly, also half of the literature is), but I think we could agree that most people would be more likely associate positive feelings to sunny Italy/Spain than to freezing rainy Finland/Denmark.

After all, mediterranean countries are still rich enough to guarantee to the majority of their citizens shelter, a job, and a peaceful life. Moreover, they are unquestionably nice places. So it isn’t unreasonable to see that higher incomes and stability don’t prevent Finns (for whatever reason) to kill themselves at rates three times those of Italians. Standard happiness leaderboards’ contrast with common facts of life; Spaniards being funnier than Danes, for example; or the fact that, even though it’s not classified as happy a place, hordes of tourists each summer flock to the Mediterranean, not to the North Sea. Nevertheless, these stats aren’t seen as puzzling, which is quite strange to us.

Our short silly exercise shone light on the fact that time use could be greatly underrated in the field of Happiness Economics, especially if compared to subjective self-reports. We don’t know why it isn’t used more extensively, both in the literature and in popular news. Self-reported scores continue to be the standard, besides them not being associated to objectively happy things like having friends or low suicide rates. Further data should be collected in order to test the hypotheses that happiness can be proxied by time use and that Mediterraneans are in reality the “Happy People” of the world.